Vida Blue has died at the age of 73. He was one of the greatest pitchers in the 1970s and was a key member of the three-time champion Oakland Athletics from 1972 to 1974. It is yet another reminder that America has changed a lot since his heyday and not in a good way.

Vida Blue looked like he was going to become one of the greatest pitchers in history early on. In his eighth major league start, on Sept. 21, 1970, he threw a no-hitter to the Minnesota Twins in first place. In the following season, Blue had won seventeen games, lost three, and had an astounding 1.42 earned run rate by the time of the all-star break. The whole country was once again enthralled with baseball. Blue drew huge crowds everywhere he pitched. Time magazine put him on the cover with the caption, “New Zip in the Old Game.”

Blue had a record of 24-8, 301 strikes outs and a 1.82 ERA. She won the Cy Young Award for the best pitcher and was named Most Valuable Player (MVP) in the American League. When I was nine, all I wanted to do when I grew older was be Vida Blue.

Then, everything went bad. The A’s skinflint Charlie O. Finley, despite the national attention Vida Blue brought to the Oakland Athletics (some things don’t change, they still have a “skinflint” owner but it is now a new guy) refused to pay Blue what he was due. The greatest baseball pitcher announced his retirement amid a bitter contract dispute. He actually stated that he would take a position as a bathroom fixture salesman. Finley and Blue reached an agreement allowing Blue to return to the 1972 season. However, the magic of the beginning was gone. After 1971, he remained a top pitcher in baseball. He had many seasons with 20 wins but never again reached the heights of his career. He struggled with drugs later in his career.

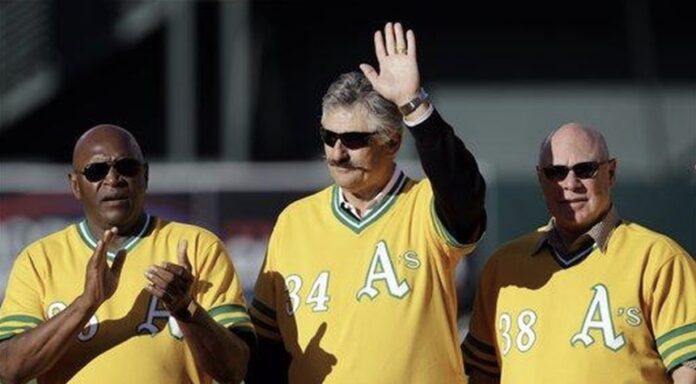

Vida Blue was a San Francisco Giants pitcher who became a Bay Area ambassador for Goodwill. He is a kind and genial person. I had the honor of meeting him a couple of times, and he was extraordinarily gracious, affable, and friendly, even when I was hyper-enthusiastically reciting his 1971 statistics to him from memory on a street in Cooperstown, the home of the Hall of Fame (which he isn’t in, but should be; he was there for an event showcasing black twenty-game winners).

Vida Blue experienced discrimination as a child growing up in Louisiana during the 1950s and 1960s. Blue complained to Finley that the owner of the A’s was treating him like a “damned colored child” during the contract dispute. However, at the same time in an America eager to leave racism behind and achieve true unity among Americans, Blue became a national icon. He was both a black and an American athlete who was loved and supported by many boys, black and white.

Vida Blue could have chosen to be gloomy and resentful, but he chose not to. He always projected kindness, warmth, and positivity, which suggested that we could still achieve our goals as a country despite the presence of race hucksters, and those who are prone to grievances. CBS Sports reports that he worked with “multiple charitable organizations to promote baseball in inner-city areas” and whatever his politics were, he kept them to himself.

Today, the hucksters who propagate grievances have won. The racial divide in America is worse than it was during the Jim Crow era. Identity politics is now commonplace. Vida Blue’s passing brings to mind the summer of 1971 when the heroic exploits of a young black man, 21 years old from Louisiana, whose name was a popular song, captivated a nation. Vida Blue stated in the Time magazine cover story: “I don’t want to break records or knock out many people. I want to win. Not yet, I’m a pitcher. I still haven’t mastered my craft. I want to be the best that I can be. I want to be an excellent professional. I want to excel at what I do. “I want to be the best.”

He was the best for that summer and brought out the good in us all. We must recover the promise that was in those days. We’ll miss you, Vida Blue.